Why We Watch Sports: Joy, Love, Pain, & the Rose Bowl

This is what sports do. They take our emotions & memories—the love & the hurt, the hopes & the losses, the smiles, tears, laughter—and distill them into singular moments capable of celebration & joy.

“We leave football, football never leaves us.”

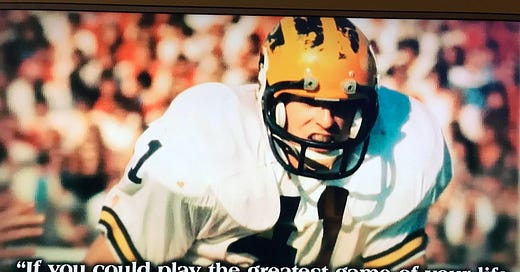

Rob Lytle

On a patch of grass in Pasadena, with mountains in the distance and the sun just retired for the night, Alabama and Michigan lined up for one more play, a final three-yard skirmish with the end zone the line to make. Only in sports can nine feet be the distance between ecstasy and another moment where your soul feels plucked from your body.

I stood in my mom’s kitchen in Northeast Ohio with a small gathering of family. In the time before the play, I thought about my dad—late Michigan running back Rob Lytle—and didn’t know whether to love him or hate him for the blessed curse of Michigan fandom.

I replayed the game. Michigan had led early, then seemed poised to lose late. They’d survived botched punts, fourth downs, and tipped passes. They had scored first in overtime, but a lifetime of cheering for Michigan said that would never be enough.

My cauldron of nerves boiled in the present and collided with emotions from the past—all the family, feelings, love, and loss that made me care so damn much about what happened next on a football field 2,400 miles away.

I looked around the room and saw Mom tucked deeply into a big-backed chair, as if hiding from an outcome she expected was coming. Mom graduated from Michigan in 1977, and she endured the emotions of game days in ways few can understand. On fall Friday nights, she would sit with a dear friend eating ice cream and speaking little, waiting for Saturday with a nervous, fearful heart.

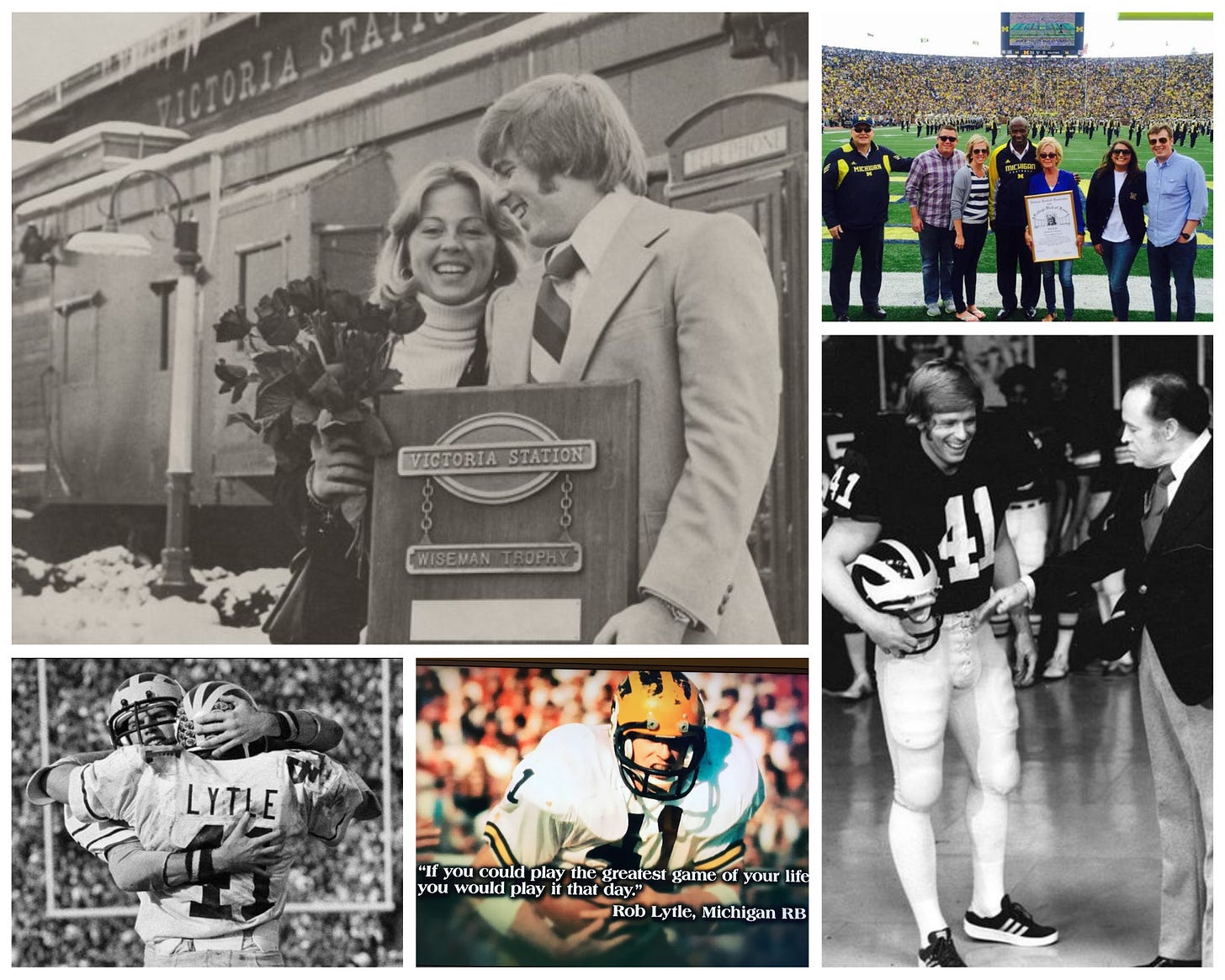

Mom started dating Dad in 10th grade. She watched and she prayed on those afternoons in the Big House. And not for yards or touchdowns, but for the person who would later become her husband of thirty-three years before he died to just be okay as he absorbed a part of the collection of collisions that proved so costly later in life.

Now, she had said few words for more than three hours and her stare never left the TV. A black lab, wearing a Michigan collar and named Bo, rested near her feet.

We all love things that make us both smile and feel deep loss in a single memory. This is Michigan for Mom. The passion is deep. The emotions are complicated.

I looked at my sister as she pressed her hands to her mouth and swayed nervously. Though she looked straight ahead, eyes fixed on the screen, they seemed somewhat distant, too.

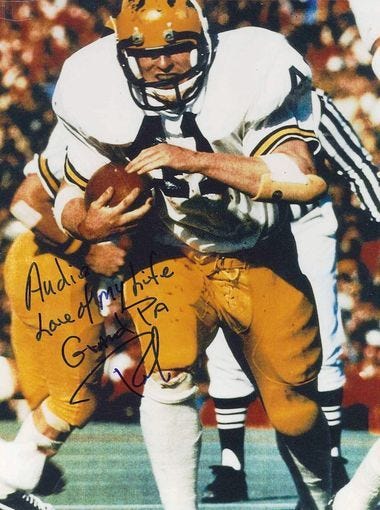

One Sunday morning, she had handed Dad two photos of himself carrying the football. She asked for his autograph on each, one to her and one to her daughter, Audrey—or Audie as Dad called her. Dad never liked signing autographs, preferring people think of him in the present and not remember him for what he was in the past.

That morning, Dad signed both photos and did so with a big smile on his face. He died six days later at fifty-six.

I wondered, while looking at my sister, if that moment ran through her thoughts as it did mine.

A timeout.

A squadron of butterflies attacked my belly. I tried to drown them with Pacifico’s, but they only got angrier as the commercials dragged on.

I closed my eyes. When I did, vignettes filtered in maize and blue began clicking like old pictures playing in a slide show.

I pictured the story I’d heard of my grandparents, my dad, and Bo Schembechler gathered around a table in a small roadside restaurant in Fremont, Ohio. Grandpa had a cocktail. Grandma smoked cigarettes. And the fiery football coach there to recruit Dad to one of the country’s top schools complained of too many bones in his perch sandwich.

“Just deal with it!” Grandma barked at the coach. “You’ll get what you get and like it.”

Bo’s recruiting pitch for Michigan was simple. He said, "At Michigan, we have six half-backs. If you come, you'll be number seven. Whatever happens after that is up to you."

Never one to miss a challenge, Dad was smitten by the maize and blue.

Sons, especially in matters of sports, tend to take the lead of their fathers. Growing up, we had a few old Michigan games on VHS. I watched these games—fast-forwarding to the good plays and rewinding the better ones, intoxicated by the sight of fall Saturday afternoons and the majesty of matinee idols—and I, too, fell in love with Michigan football.

On October 30, 1976, Michigan played Minnesota on a gray and rainy Halloween Saturday. The crowd came decked in costumes while Minnesota tried to impersonate a worthy opponent. As a kid, I’d watch the introductions to see heroes donning winged helmets run from the tunnel and tap the M-Club Banner. Watching this tape is how I met Keith Jackson. I’m forty-one now and still hear his voice calling plays in the Michigan memories my mind can’t help but replay.

On January 2, 1989, Michigan beat USC in the Rose Bowl. We had this game on VHS, too. Leroy Hoard won MVP that day, but my favorite play—the one I imitated while darting around couches and dodging chairs in my living room—was a reverse by John Kolesar (at 30 seconds in the clip).

In the starting to set California sun, John spun, fought, and sprinted for yards while Keith Jackson (that voice, again) called the play. I’ve seen this run hundreds of times, and I smile every time I see it again. It reminds me of being young, wanting to play football, and Michigan winning.

When Michigan beat UCLA on a last second field goal in 1989, Mom, Dad, my sister, and I held hands watching on a small, black and white TV.

When Colorado stunned Michigan in 1994, Dad and I were just outside the Big House. He’d wanted to leave early to “beat the traffic, since Michigan had already won.” I was twelve and told him it was his fault they lost, that he had ruined everything.

When Charles Woodson, the Fremont, Ohio, legend, sprinted past Ohio State and into the end zone in 1997, Dad and I were tossing a small football in our basement. Dad watched, a smile spreading across his face. “Best to ever do it,” he said and pointed at Woodson on the TV.

Alabama or Michigan called another timeout.

I sipped a Pacifico and tried to breathe while the vignettes continued to play.

We’re in Grandpa’s station wagon driving north from Ohio to Ann Arbor. A sea of maize and blue greets us when we get close. We step from the car into a crisp, November morning and onto a grass field dressed in a layer of frost. Leaves, green most of the season, now come clad in red, orange, and yellow.

Smells of chili, burgers, cigarettes, hot dogs, and hope for the game fill the air. Footballs fly over and around cars. Soon, we’ll watch the band make a ‘Block M’ and march across the field. The sweet, sweet sound of The Victors will play while I sip hot chocolate.

The vignettes run like scenes from a Disney movie about growing up in the Midwest—full of fathers, sons, football, and family. It’s like Rudy meets Field of Dreams meets the Griswold’s, or something like that.

Whatever it is, it’s fall, it’s Michigan, and it’s perfect.

Finally, Alabama and Michigan line up. I take a final moment to look at my mom and my sister and think about my dad. The emotions of the present connect with those from the past, all of it coming together in one more play.

My mom, sister, and I might bleed maize and blue. But Dad bled for the maize and blue. He racked up yards and touchdowns, leaving Michigan a Big-10 champion, Big-10 MVP, and the school’s all-time rushing leader. Decades later, he entered the College Football Hall of Fame.

But, despite all the accolades, he cared about the team and about winning. He left without a National Championship and lost to USC in his last game. The final shot of him in a Michigan uniform, on the sidelines of the 1977 Rose Bowl, is someone wounded but still trying to smile through the pain. He never said so, but I know he always felt he had let his teammates—and Michigan—down.

This is what sports do. They take our emotions and memories—the love and the hurt, the hopes and the losses, the smiles, tears, and laughter—and distill them into singular moments, moments when the fight for three yards feels like it counts for everything… and so much more.

Our family carried these feelings into the final play. Then, as the whistle sounded and Michigan stormed the field to celebrate, my mom, sister, and I embraced in a tangled mess of nostalgia, love, bittersweet happiness, and family.

We’d embraced like this before, when so overcome with emotion each of us needed the other for support. That was on November 20, 2010, seconds after we learned Dad had died.

That embrace was one of sadness and heartbreak.

This was one of happiness and joy.

Fourth and goal from the three-yard line. One snap, not even for a national championship, but somehow for much more.

Sports do this, too. They create new memories, not to replace the old ones but to give us something new that smiles alongside them. They create moments of joy in the present, connected with love in our hearts to the past.

On Monday night, we’ll be watching again. Pacing, holding hands, and waiting. Three hearts hoping for another moment of joy together.

Sports can be powerful this way.

What an amazing story of your family and Michigan football history! I also graduated in 1977 and Rob Lytle was an icon. I always loved to watch him carry the ball. He defined “Michigan” along with Bo and so many other true legends. He was taken from his yo far too early but he’s watching the game n the biggest screen in the universe! Go Blue!!!

Great read as usual Kelly. Knowing the ride well from the Fremont vs Sandusky days to the OSU vs the TTUN days, those emotions stay intact for a variety of reasons. While not relishing all of what those past memories bring, they remain a part of us, both the good and the bad. Congrats on the championship and the anticipation for next season already begins, along with past emotions that will once again accompany us during the journey.