A Friday in October

I wrote my dad's eulogy two years before he died. This is a story about football, fathers, sons, and reckoning with a sport I love but one I hate, too.

Picture a football play.

Chin straps buckled. Shoulder pads snapped.

Eleven players line one side of an imaginary line dressed in their best battle armor staring down eleven on the other side ready for a fight. Boys who want to be men. Men trained to be warriors through the echo of every whistle.

When it’s cold, the smoke from rapid breaths sneaks through small openings in face masks. When it rains, helmets glisten a touch more under bright lights. Someone has a bum ankle. Someone else a knee full of cortisone or shoulder shot with Toradol.

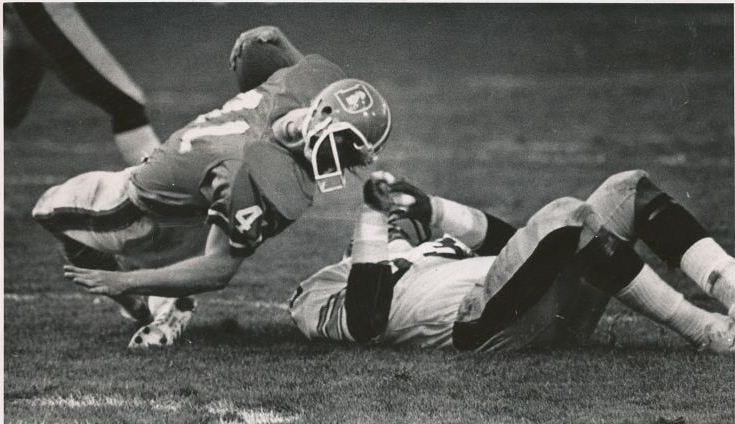

Twenty-two players - squadrons of bodies, brains, aches, pains, tau buildups, and twisted fingers - all coached and conditioned to sacrifice their tomorrows for a glorious today between the white lines.

At the snap, a ballet of fancy-footwork plays out in tight quarters according to scripts written to inflict violence. A guard pops the inside shoulder of the tackle across from them, then rises a level to crunch another body. A linebacker shoots a gap. A safety torpedoes toward the melee. A wide receiver hunts a crack back. An end sets an edge, their heels digging into dirt, and holds the line until reinforcements solidify their position in the trenches.

A quarterback surveys the carnage with a trained eye. They give to a runner who seeks escape through the narrow slivers open in the enemy’s defense.

We stand in crowds to yell and cheer. At home, we holler at a bunch of pixels in high def. Some parents hold their breath - watching, waiting, and hoping - to see their sons pop from the pile, while spouses count the hits and wonder what pain comes later from right now’s joy.

The whistle blows. One play. A dance of destruction over in mere seconds. And, then, we wait.

Players, coaches, parents, pundits, partners, and fans all craving another fix of whatever smack football has us hooked on.

As a kid, I loved watching my dad watch a football play.

He’d bend on creaky knees, crouch low, and measure offensive line splits in his head. He’d shuffle, some, in place, and his fingers would twitch at his sides. A stream of brown Levi-Garrett would shoot onto green grass, and his eyes would get so focused it looked like he might burst onto the field.

“Did you see that center’s first half-step?” Dad would say after a play. “Six inches. Pitch perfect. And that punch. Outside edge of the inside shoulder. Damn that was good.” He’d smile and bounce in place waiting to watch whatever came next.

Most kids never see what truly makes their fathers tick. But with my father, it was easy.

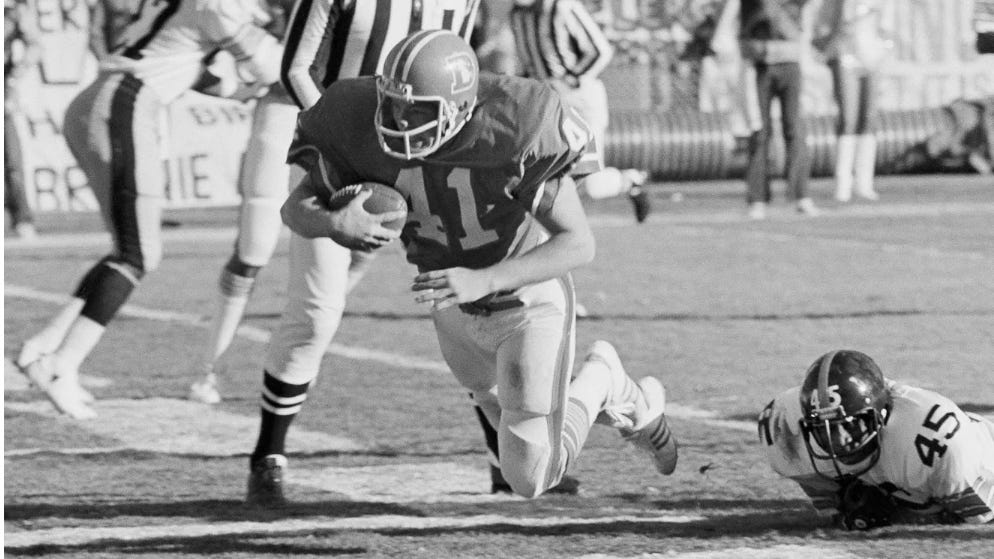

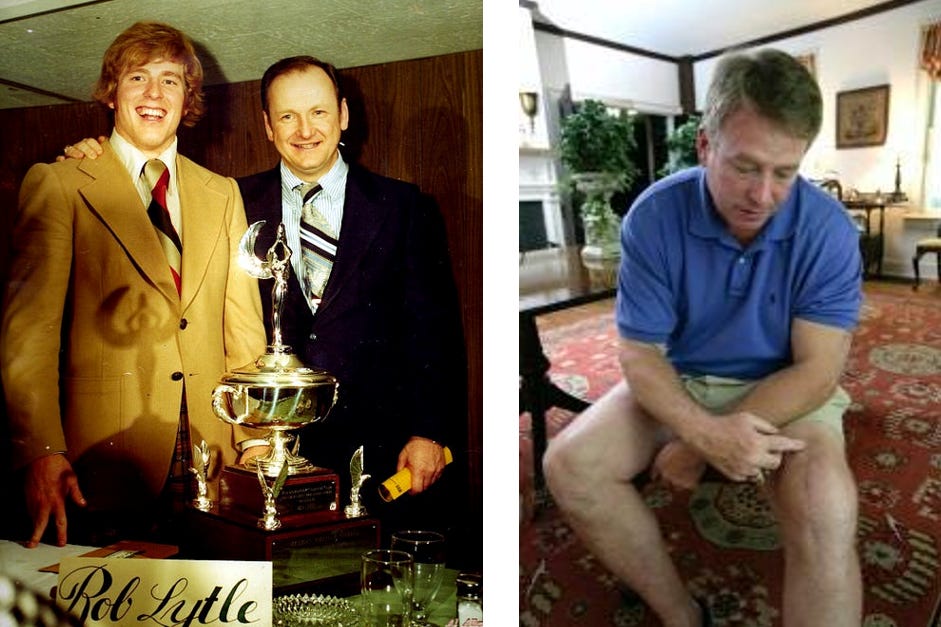

As a ten-year old, Dad walked around with close-cut reddish hair and freckles while wearing ankles weights and carrying a football wherever he went. He told his older sisters he’d one day run in the NFL. Same for his teachers. Football, for Dad, was magic, and the magic of football was in the minutiae of each football play.

The last time I watched Dad watch a football play happened on Friday, October 3, 2008.

That night, we traveled to Findlay, Ohio, to watch our old high school play for the first time together in many years. The temperature dipped below fifty by kickoff, and we wore sweatshirts under light jackets while watching from the sidelines because Dad knew someone who knew someone who didn’t mind us hanging near the action.

The sky turned dark and the blackness outside of us shielded the stadium from the rest of the world. Bright lights beamed onto the players below. Pads smacked and shoulders crunched. Bands played their hits from the stands while fans on each side took turns cheering the plays their team did well.

Dad did what he always did and lost himself in the game he’d always loved.

He clapped for both squads. Grimaced when a running back missed a cut. Made me marvel over and over with him at the two-step danced by the big boys on the offensive and defensive lines. His smile never left his face, and I knew that if life could grant him any wish it would be to somehow run on that field one more time.

One thing I’ve always loved about Friday night football is how the rest of life disappears when you’re watching it. It’s as if only the game, and whatever’s playing out on the field, exists in that moment.

For a few hours that night, time stood still for Dad and me. We got to feel like kids again, with Dad watching the game he loved playing and me remembering the specialness of watching my dad watch a football play

The drive home took us along a two-lane state route, and we rode mostly in silence. The energy of the night had faded, and I sensed a change in Dad, too.

Halfway through the drive Dad turned to me and said:

“Kelly, I don’t know what it is, but I’m so tired all the time.”

His words hung in the quiet space between us for a moment.

Then, he added, “But it’s okay. I’ll get through it.”

I stared out the window for what felt like forever as we clipped along a flat stretch of land in Northwest Ohio. Dad’s voice was somber and resigned as he spoke, and his shoulders slumped. Although I couldn’t see his face, I knew how tired it now looked.

Dad had always been invincible. Now, he seemed to be struggling to reach the next quarter of a game getting harder and harder to play.

“I know you will, Dad. You always do,” was all I said.

Dad limped up the stairs when we got home. He leaned hard onto the handrail, and it screamed for mercy under his pressure as screws and joints pulled from the wall. He put each foot on each stair and paused before taking each step. Slowly, he made his way, a still young man now a far cry from the runner who’d once won Big 10 MVP.

A few hours later, I sat at an old desk in my childhood bedroom and thought about the night, the drive, about football, and about my dad.

I saw the right shoulder he couldn’t lift and the pinky that pointed at a right-angle.

I pictured his old Michigan helmet, the one with chipped blue paint and clipped maize wings, and saw the scars etched into the armor he wore to battle for those glorious fall Saturdays that could never last long enough.

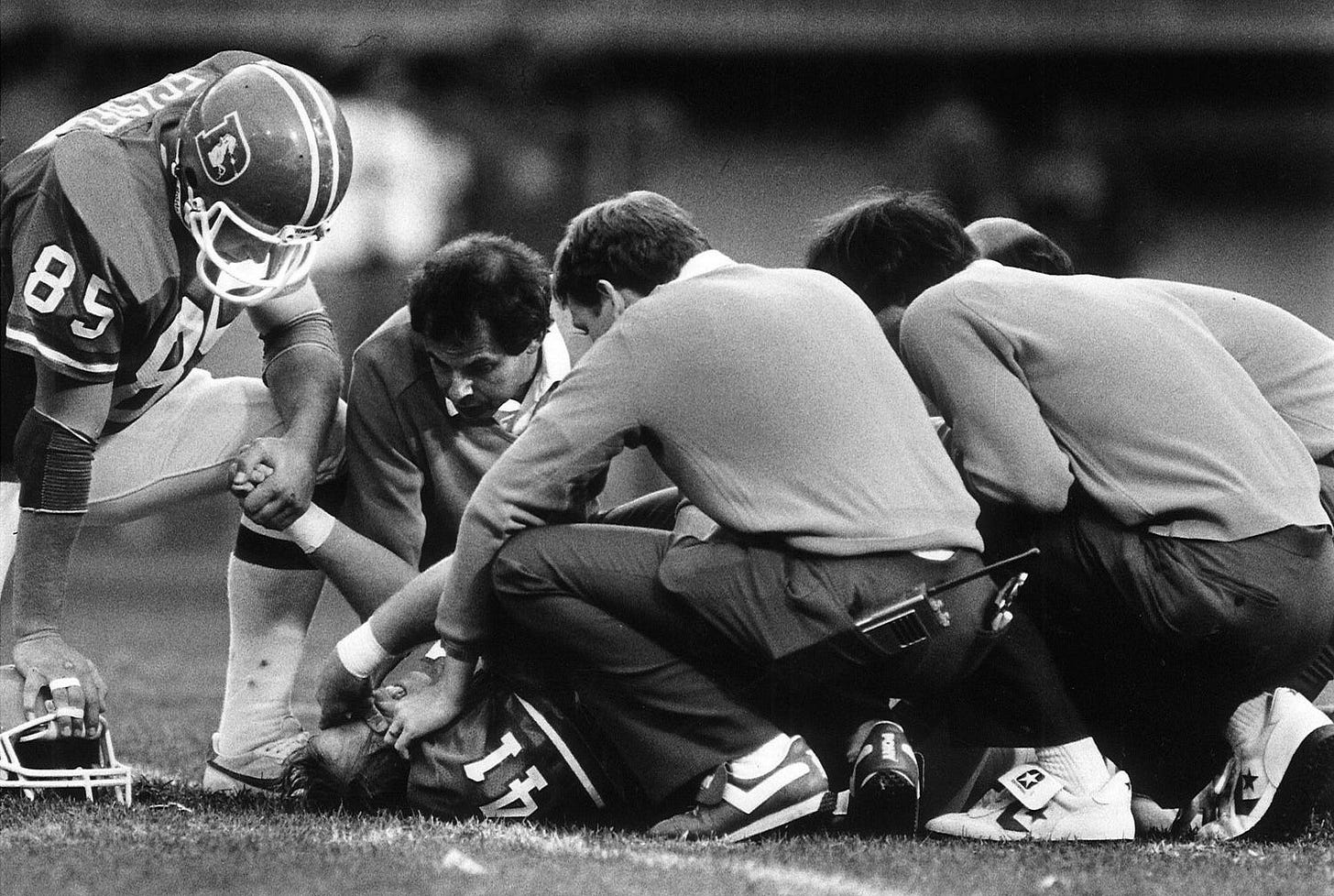

I remembered the thirty-plus operations, double digit concussions, and thousands and thousands of high-speed collisions he talked about enduring.

I saw all the receipts he kept from his prescriptions, refill after refill of helpers meant to silence screaming nerves and given to him for decades like they were f*****g Luden’s Cherry Cough Drops and not narcotics.

I thought about football, this violent and seductive game, and the deal Dad had made with its devil.

I knew Dad would fight for as long and hard as he could because that’s who he was. But I realized, then, the somberness I heard in his voice and the exhaustion I felt in his words, wasn’t him giving up or asking for help, it was him knowing, deep down, that he’d already been beaten by a life sacrificed to football.

I don’t know why, in life, the things we fall hardest in love with can be the things that bring us so much pain, too. Dad loved football, and I used to love watching my dad watch a football play.

That night, sitting alone with tears running down my cheeks, I wrote a bunch of words about my father. I read them, then, as the eulogy at his funeral just two years later when he died at fifty-six.

A heart attack had killed him, but only because he’d lost his life to playing football.

Football, a game I’ve never not loved, but a game I f*****g despise, too.

See you when we see you

Friends, in a few weeks I’ll announce my next project and how you can help.

It’s about the duality of football and loving a game I want to hate.

We love you, and we’ll see you when we see you.

Well done.

Kelly, so wish I could have some time back with your dad. This story was exceptional. He's come up in so many stories with friends lately. Love you. Try to make it to Fremont before Christmas. We'll even agree to invite Lewie.

Love, Kim